"It's a dangerous business, Frodo, going out your door. You step onto the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there's no knowing where you might be swept off to."

-J.R.R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings

But more and more recently, I have been noticing just how easy it is to become a slave to reading. It's not just for books anymore. Reading material is everywhere these days-in our books, on our phones, on billboards, in the doctor's waiting room, and our computer screens. I am generally a voracious reader under normal conditions, but when stress is added to that mix, I am especially susceptible to reader's binge. Somehow, I have still not perfectly mastered control over the backwards instinctual logic that attempts to remedy stress and excessive mental preoccupations with adding yet more preoccupations to the mix. In the midst of perusing too thoroughly the latest in the Catholic blogosphere, my Twitter feed, the newly arrived issues of professional association publications, and the rest of todays news, and eyeing the books on my tea-tray, I had to stop myself.

|

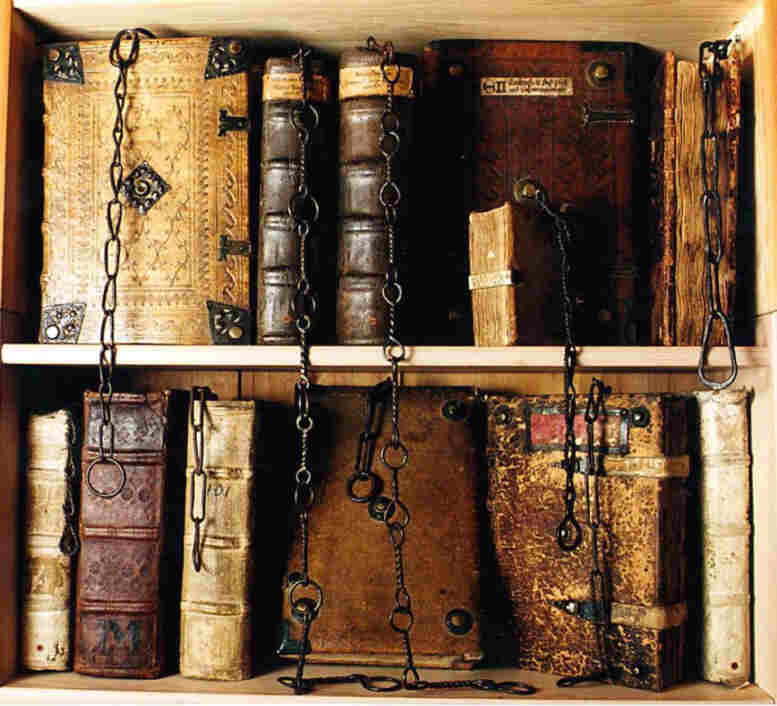

| Sometimes we are more chained too books than we realize. |

The 'problem' of reading is a complex one. Contemporary society is awash with the lingering Enlightenment ideal that knowledge and education will improve society. There is also a lingering, and largely mistaken, subtext that suggests knowledge is power, more knowledge is equal to wisdom, that knowledge, when acquired in larger quantities, and including a larger range of subjects, has a correspondingly larger goodness. More, and broader, knowledge can produce some pretty wonderful things. The recent landing of the Mars rover Curiosity is a great example (if you haven't yet seen the video, do yourself a favor and watch here). But more knowledge does not necessarily produce more goodness-and if the saints can serve as any example, heroic virtue doesn't depend on a heroic level of knowledge.

Our society thus puts a premium on education. Millions of students and parents are now willing to go billions of dollars into debt for that 'coveted' diploma. There is seemingly nothing too valuable to sacrifice to acquire an education. I'm not concerned here with exploring measures of higher education, but what I am concerned about is a related attitude that many people have towards reading. If we're lucky enough, most people, from a very young age, are heavily encouraged to develop reading habits and acquire an affinity for reading. Some of my best childhood memories are of the spoils I would haul home from the library during the summer months. I'm all for encouraging childhood literacy, and am still occasionally sobered by a reminder that adult illiteracy is still a problem in our country, let alone the world at large. But what often accompanies this nearly universal encouragement of reading is the sentiment that reading is an absolute good. That certainly has a nice ring to it, but if we subscribe to it we are kidding ourselves. "Oh, well, my daughter wouldn't read anything before 'Twilight', so I'm just glad she is reading now!" gloats many a mother these days. To which I'd like to reply: "Well, my baby wouldn't touch any food until he wandered across this tasty poison the other day, and I'm just glad he's ingesting something, so I'll live with it!"

'Tis better not to eat, than eat poison. And we wonder why our country has a problem with obesity. But I digress.

My point is that it is just as easy, if not easier, to develop an 'obesity' of the mind than an obesity of the body. What is at stake is not a question of learning, which is undoubtedly a good, but of consumption. Reading is indeed connected to learning, but if children-if anypeople-are encouraged to read, regardless of content, they are being taught not how to learn, but how to consume. How to be just another cog in the information-processing machine. As life is a process of constant conversion, it is important to have daily or regular habits of learning about the world, and, whether you subscribe to religion or not, learning more about your faith or [non-] philosophical worldview. But it's all too easy to make this activity an act of consumerism too. Yes, all these blogs, articles, books, etc. may be good, but is my daily intake simply another dose of consumerism, an empty affirmation of the thoughts I would like to have running through my head? A distraction from the here and now, the real? Am I ingesting, rather than living?

At what point does this:

become this?

In light of this, the endless chorus of libraries' "Read!" campaigns can seem like just another call to develop our consumerists abilities. Usually these efforts are made in good faith to improve literacy, help communities, and foster educational progress, but we ought to be more explicit about why we are reading. This doesn't need to unravel into a heated debate over educational ideology, but it does need to acknowledge that not all materials are of the same benefit. Eating-regardless of the substance, isn't an absolute good, and reading isn't either. Such an advisory system shouldn't amount to a book-banning nanny state, but I think we would all benefit from something like a "Beware, all ye who enter here" at the library door.

My ultimate point in piddling through all this is that to promote the goods of reading also requires encouraging readers to not read all the time. In my case, thank goodness for prayer and the demands of the workday, otherwise there are times at which I would probably read until my eyes fall out. Acquiring the goods of reading requires temperance and prudence, which are too often seen as vices today. "Why burden yourself with restrictions?" Well, as the old story goes, the barricade exists to keep the tsunami from harming the natives, and if it keeps out some other parts of the outside world, it will likely be a worthwhile sacrifice.

I sometimes marvel at my students' knowledge of Harry Potter combined with their lack of having read anything of more eternal worth (thankfully, either the Twilight generation has yet to reach me, or their Catholicity and/or intelligence has lessened its popularity).

ReplyDeleteThat said, my own reading experience is equally bad, for the most part. All through grade school, I read mostly whatever could help me most efficiently acquire the most Accelerated Reader points (a program I believe has had horrible effects on actual literacy). This amounted mostly to the Boxcar Children and, later on, the Hardy Boys (though I did read a few abridged classics). In junior high, it was all Star Wars novels, then in high school it was mostly hit-or-miss until I encountered Chesterton my senior year. So not much in there beyond the level of Rowling, and thus I don't have much to complain about. That said, this did not follow me into college, which doesn't really seem to be the case for many of today's students.

I'd mention what we read in the actual curriculum if it amounted to anything at all.

At any rate, you are absolutely right.

Do you actually have Logos? It's so tempting. If only it were actually affordable...

I don't have Logos, but I keep hearing amazing things about it. I hope that most theological libraries get a copy into their reference collection.

ReplyDeleteAccelerated Reader was a big thing when I was in grade school too. I think at lower grades, and at an earlier stage in its development, the point system worked as a decent motivator, with at least some classics/good substance. But looking at an AR list now, I hardly recognize many of the titles. I know I'm not a YA librarian, but the good titles of just a decade ago can't have faded in value that much.

I think that some awful point-inflation occurred when the Harry Potter books were published-I remember being in middle school and making a good attempt at reading Moby Dick, since it had a high reading level and a very high point value compared to most other titles. Somewhere in the 40s, I think. On average, most other books of decent heft were maybe in the 17-25 range. Then the Harry Potter series comes along, with the 'thicker' volumes worth around 35. If students get more points for Harry Potter than Huck Finn, The Hobbit, Invisible Man, and The Count of Monte Cristo, then what are going to choose to read? Even if they are more work for teachers, old-fashioned book reports are still the better way to go, in my mind.